- About

- Visiting

- What’s On

- Venue hire

- Catalogues

- Collections

- Belle Vue – search archives catalogue

- Digital Resources

- Art Treasures Examiner of 1857

- Manchester Association for Constitutional Order

- The North Western Museum of Science and Industry: Some Reminiscences by Richard Hills

- Criminal Manchester

- The Cup of Destiny

- Athenaeum Souvenir

- Middle English Manuscripts

- Manchester and Liverpool of Today

- Hollingworth’s Mancuniensis

- Memoir of Cecil Wray

- William Seward’s Diary

- The Anti-Monopolist

- Fishwick’s History of Rochdale

- Knyvett’s Defence of this Realm

- Tractatus de Nigromantia

- Axon Ballads

- Prints and Photographs

- 101 Treasures of Chetham’s

- Printed Books & Ephemera

- Archives & Manuscripts

- Blog

- Support us

A Small World?

In mid-March 2020 we were planning to exhibit some of Chetham’s Library’s early atlases, to provide an insight into how knowledge of the world was expanding in the late 16th and early 17th century. Before we could get the volumes off the shelves and into display mode – whoosh, lock-down came and our own worlds began to shrink. It’s interesting to consider, in these strange times, the contrast between the lives and work of the intrepid explorers who brought back new information, and the networks which linked them with the small and specialist world of mainly desk-bound mathematician-cartographers who used the new information to create the most astonishing and beautiful maps.

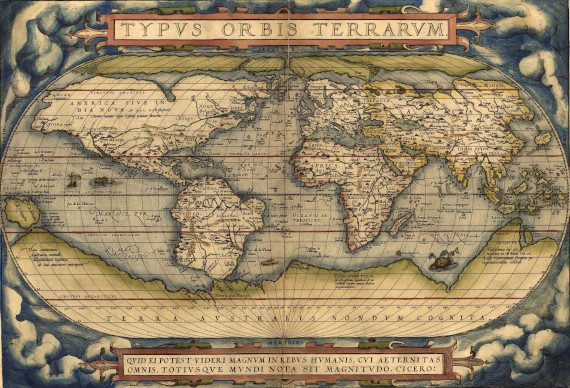

In 1570, map and book-making history was made when Abraham Ortelius, a Flemish book collector and engraver published the Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, often known as the first world atlas. Although sheet maps had been in existence for centuries, it was only now that they bagan to be bound together in book form.

Chetham’s library has no copy of this great book but it does have a 1596 edition of Ortelius’s weighty geographical dictionary, the Thesaurus Geographicus, which was an explanatory volume. However, we do have editions of the work of his compatriot, friend and colleague, Gerardus Mercator.

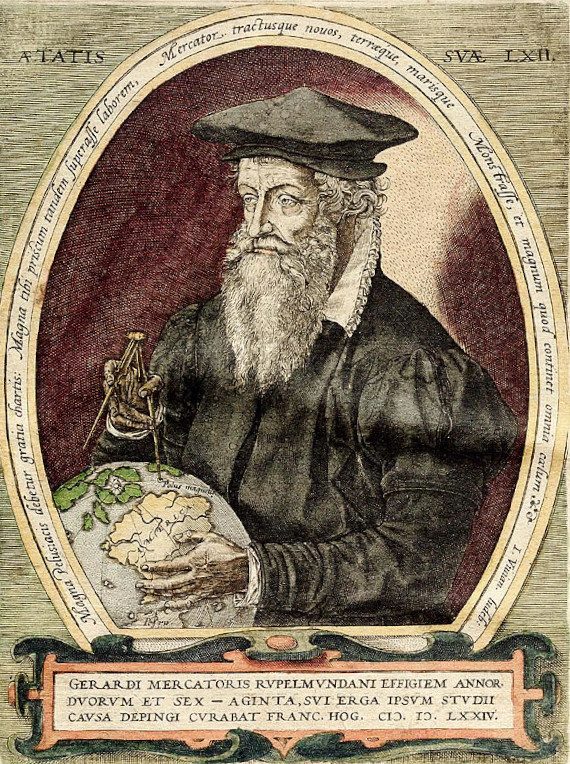

Mercator was an armchair cartographer who used his mathematical and calligraphical skills to present information attractively, if soberly, on his maps. His fame rests primarily on the map projection, first printed in 1569, named after him and still in use today. Despite the distortion near the Poles, it accurately depicts the shape and direction of land masses and sailors came to rely on it. His work also enshrined the convention, started by Ptolemy, of putting North at the top – a convention which is only now being questioned because of the colonialist implication it may carry of the superiority of northern lands and races.

As Ortelius was producing his World Atlas in the 1570s, Mercator was working on the first Atlas of Europe, at the behest of the heir to the Duchy of Cleves who needed a decent guide-book for his forthcoming European tour. In order to produce it, Mercator cut up several examples of his own wall maps of the world, Europe (1554) and Great Britain and Ireland (1564), adapting them to a book format. Later, he added hand-drawn scale-bars and titles and then supplemented this collection with printed maps published by Ortelius himself. He didn’t live to see the finished version, but Mercator’s Atlas was finally published by his family in 1596.

The small, scholarly world of Mercator and Ortelius was also inhabited by a far-from shadowy figure who provides a link with Chethams. John Dee, a celebrity in his day as now,renaissance scientist, astrologer, alchemist and occultist, was appointed late in life, from 1595 until his death in 1609, Warden of the Collegiate Church (now Manchester Cathedral). It is even thought that the young Humphrey Chetham may have met Dee during this time, and in turn there is a link between Dee and Mercator, evidenced by surviving correspondence between the two men.

Dee was 19 when he first visited Mercator in Louvain and registered as a student there. Coming back to England after three years, he brought maps, globes and astronomical instruments and in return furnished Mercator with the latest English texts and new geographical knowledge arising from the English explorations of the world. Thirty years later they were still co-operating, Dee using Mercator’s maps to convince the English court to finance Martin Frobisher’s expeditions and Mercator still avidly seeking information about new territories. In the late 1570s, Dee was disseminating some extraordinary claims that a vast tract of the northern globe had once been conquered and ruled by King Arthur, and that Queen Elizabeth thus had the right to establish an empire there. Mercator wrote to Dee in 1577 providing notes based on his own researches to support this theory. Some scholars are still on the trail of King Arthur’s occupation of Greenland and North America.

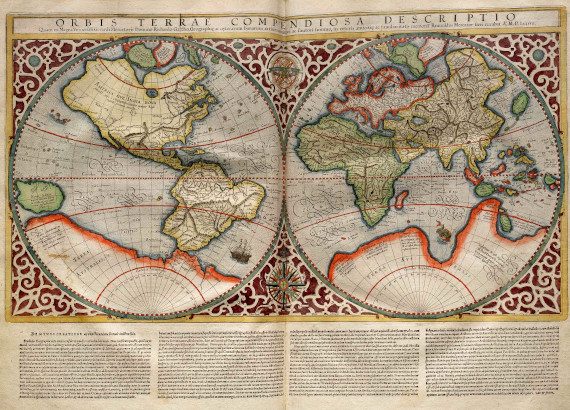

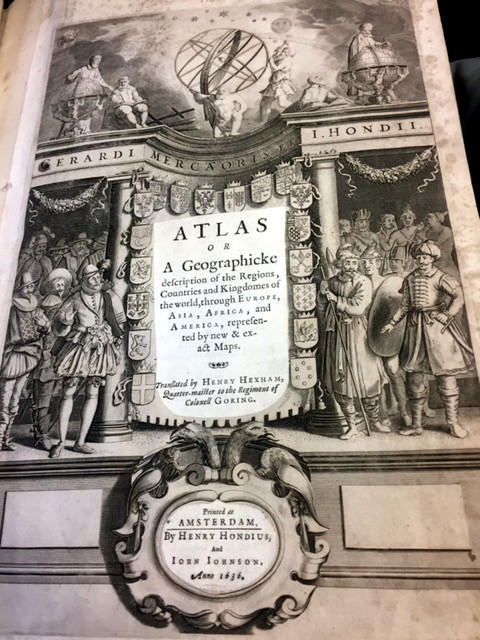

Mercator’s Atlas did not sell as well as the more sophisticated work of Ortelius. And yet it was Mercator in the end, rather than Ortelius, who became the more famous. This was largely due to an entrepreneurial Flemish engraver, Jodocus Hondius, who in 1604 bought the plates of the Atlas from Mercator’s grandson. He went on to republish it with thirty-six additional maps, including several of his own. It is the Hondius version, published in Amsterdam in 1623, which was acquired by Chetham’s library in 1693.

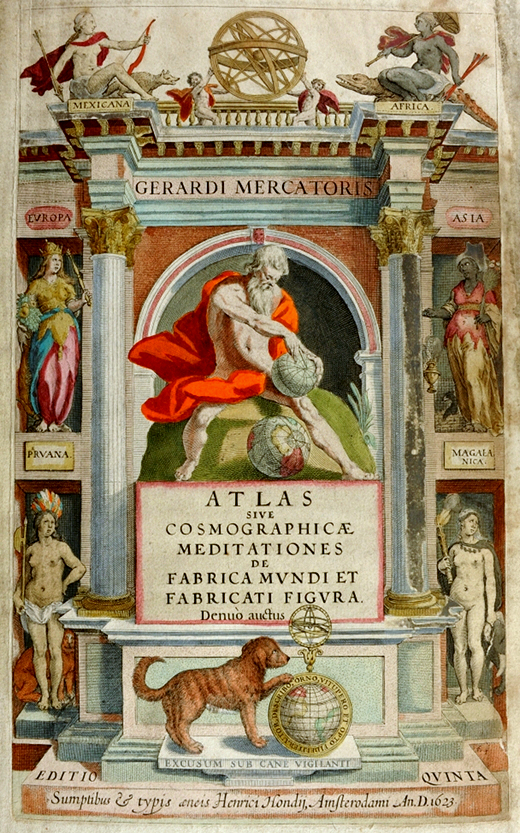

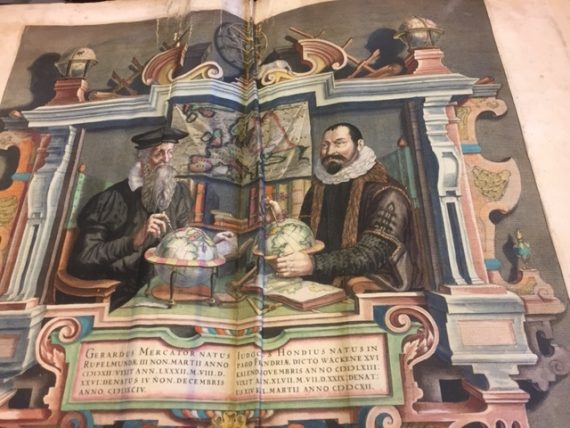

The title page of this volume carries weighty symbolism and classical allusion, but is softened by the friendly creature with its paw on the globe, captioned ‘printed under the watchful dog’. It is made generously clear that this is the work of Mercator, the name of Jodocus not appearing at all, and his son, Henricus given a mention only in the very small print. After the title page, however, we are treated to a more assertive representation of Jodocus Hondius where he gives himself equal billing with the great man. The pair are shown fancifully sharing a study and wielding their compasses and globes. Hondius would have been in his early 30s by the time Mercator died at the age of 82 and it is quite possible the couple did meet, if not in quite such a heavily symbolic setting.

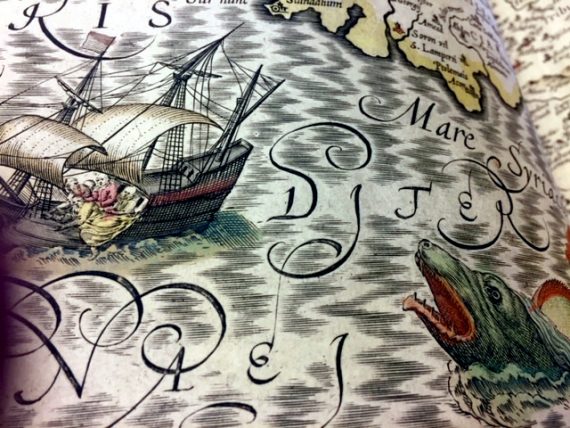

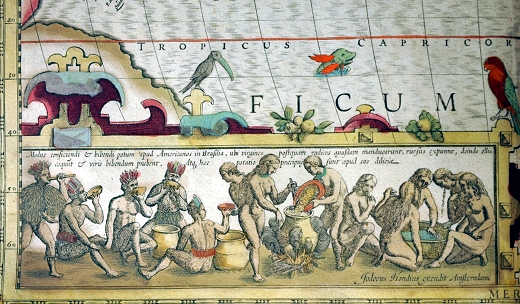

Many of the maps in the 1623 Atlas are surprisingly detailed and accurate, but Mercator and Hondius made no bones about the actual and imagined dangers of sea travel and exploration.

Such dangers might take the form of shipwreck, attack by monsters, or, for the very unlucky, both.

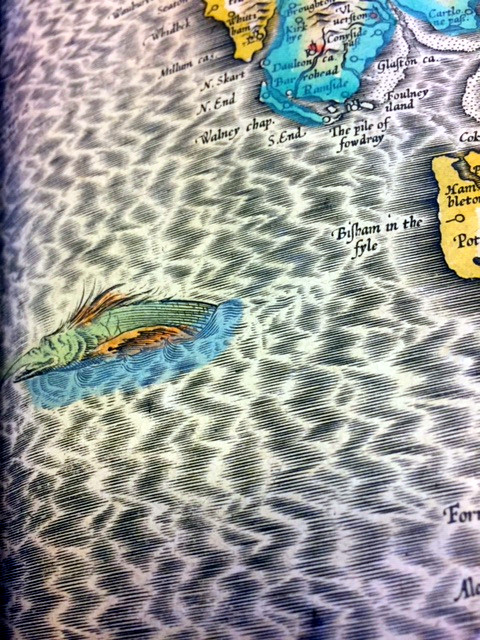

A more local illustration shows a hairy and anthropomorphised creature apparently making its escape from the Fylde coast.

And something more self-sufficient allows a galleon safe passage in the Irish Ocean.

Hondius himself was a distinguished figure in the mapmaking world. He grew up in Ghent and became established as an engraver and instrument maker there and in Amsterdam. In 1584, to escape religious difficulties, Hondius moved to London, where he was instrumental in publicising, through maps, the work of Frances Drake, who had circumnavigated the world in the late 1570s. It is very likely that Hondius too would have met John Dee during these years. Hondius was a skilled artist and at least two portraits of Drake, now in the National Portrait Gallery, are attributed to him.

The new edition of Mercator’s work was a great success, selling out after a year. Hondius’s sons later successfully published further Latin editions, as well as a pocket version, Atlas Minor. Hondius died aged 48 in 1612 back in Amsterdam. His publishing work was continued by his widow, two sons, Jodocus II and Henricus, and his son-in-law.

Chethams Library also holds a later version of the Atlas, still credited to Mercator and based on his work. The difference is that it is an English translation of the Hondius edition by Henry Hexham, a distinguished army captain. Hexham was a prolific military writer, providing accounts of sieges, battles and campaigns. Perhaps the most intriguing of his titles is A Tongue Combat lately happening between two English Souldiers … the one going to serve the King of Spain, the other to serve the States Generall

Copious English and Nether-duytch Dictionarie, of which Chethams also has an early copy.

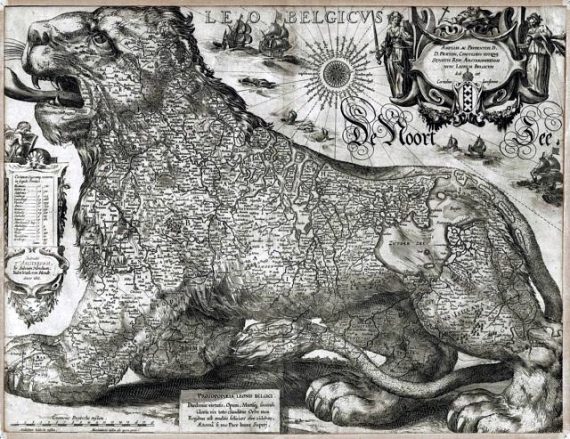

These and other Dutch and Flemish cartographers who made such important contributions to the science and art of mapmaking inhabited the small world of ‘the Low Countries’, centred on Antwerp and Amsterdam and often depicted on maps and in heraldry as the ‘Leo Belgicus.’ Jodocus Hondius made his own spectacular version of this in 1611.

As Dutch, English, Spanish and Portuguese adventurers roamed the world in search of gold and glory, the cartographers, men of science who created works of art, inhabited their own small world of curiosity and co-operation, often in the context of flourishing family businesses. Finding ourselves as limited in our travel capacity as the Flemish cartographers were and inhabiting just as small a world bounded by monsters of reality and imagination, we are driven to flights of fancy. Imagine a Zoom screen with Ortelius, Mercator, Dee, Hondius, Hexham and others sharing their ideas against a backdrop of wall maps and Dutch interiors…

4 Comments

Brian McGucken

What a shame this can’t take place. I would love to have seen the items from your collection. Thanks for the blog which whets my appetite even more!

Perhaps you will re-schedule in 2021.

ferguswilde

Thanks, Brian, glad you enjoyed it! We may well do the ‘physical’ version of this once we’re back in and firing on all cylinders, as you suggest. We’ve only a tiny amount of space in one case to exhibit things, but we will try to improve on that situation in the future.

Geraldine Beare

Wonderful – and yes – a Zoom with all those men contributing would indeed be intriguing. And I do hope you will be able to re-schedule for next year.

ferguswilde

Thanks, Geraldine! So far all email to Mercator has bounced, he may have changed ISP. In the absence of the Zoom, we will try to make sure of a map-themed exhibition when we can.