- About

- Visiting

- What’s On

- Venue hire

- Catalogues

- Collections

- 101 Treasures of Chetham’s

- Digital Resources

- The Flowers of Histories

- A Book of Hours from France

- The Manchester Scrapbook

- Thomas Barritt of Manchester

- Art Treasures Examiner of 1857

- Manchester Association for Constitutional Order

- The North Western Museum of Science and Industry: Some Reminiscences by Richard Hills

- Criminal Manchester

- The Cup of Destiny

- Athenaeum Souvenir

- Middle English Manuscripts

- Manchester and Liverpool of Today

- Hollingworth’s Mancuniensis

- Memoir of Cecil Wray

- William Seward’s Diary

- The Anti-Monopolist

- Fishwick’s History of Rochdale

- Knyvett’s Defence of this Realm

- Tractatus de Nigromantia

- Axon Ballads

- Printed Books & Ephemera

- Archives & Manuscripts

- Prints and Photographs

- Blog

- Support us

John Dee and the Tudor College

At around midday on 15 February 1596, following an arduous journey by road and water, John Dee arrived in Tudor Manchester. Five days later, he was installed in a (presumably chilly) ceremony as warden of the town’s collegiate church, now Manchester Cathedral, and it cannot have been long after that he realised the college that he had come to preside over was a poor and fractious one. Dee’s wardenship was marked by strife and financial hardship for the college and himself, and in September 1597, he wrote to his friend, Sir Edward Dyer, to complain about the ‘most intricate, cumbersome, and (in manner) lamentable affayres & estate of this defamed & disordered colledge of Manchester’.

The causes of the college’s disordered state during the late sixteenth century were diverse and overlapping, but the chief was confusion over the college’s possessions that stretched back to the middle of the century. As a secular-clerical foundation (a foundation staffed by priests rather than monks), the college had weathered Henry VIII’s dissolution of the monasteries, but its fate was sealed during the early years of Edward VI’s reign by the Chantry Act of 1547. According to this act, the college was dissolved, its lands were seized by the crown, and the fellows were pensioned off. When the college was refounded by Mary in 1557, it was re-endowed with its former lands, and some of the fellows who had been there before the dissolution returned again. One of these was the future warden Laurence Vaux, a Catholic recusant who refused to swear the oath of supremacy following Elizabeth I’s ascension just two years later. By the time the queen’s commissioners visited the college in October 1559, Vaux had already fled to the continent, taking the college’s previous silver plate, vestments and muniments (the title deeds to the college’s properties) and hiding them with the local Standish family in an attempt to frustrate the aims of the Protestant reformers and set the stage for the college’s eventual Catholic restoration.

Figure 1: The medieval quire of Manchester Cathedral, formerly the town’s collegiate church.

In 1561, Elizabeth appointed Thomas Herle as the college’s warden. It is difficult to judge this warden’s character, since half of the scholarly literature on him claims that he was tasked with stripping the college of its properties and leasing them to the queen, while the other half sees this as a prudent action that set the college on a firmer legal foundation while guaranteeing an annual rent from the crown. Meanwhile, other properties were leased locally for periods of up to ninety-nine years, securing lump sum payments to the warden and fellows at the expense of the college’s long-term income. Herle spun such a convoluted web of leases that it became hard to know who the rightful tenants of many properties were, a problem that was probably exacerbated by Vaux’s action in 1557. In any case, Herle proved unpopular as warden, and following a petition from the town’s parishioners, Elizabeth re-founded the college in 1578 under the new name of Christ’s College. At the same time, she reduced the size of its community by half, possibly because the college’s income was by then insufficient to support a larger community: during the late sixteenth century, several fellows had to support themselves through medicine, law and even hospitality. Herle was pensioned off when the college was re-founded, although it has been suggested that he continued to cause trouble during the subsequent wardenships of John Wolton (1579–80) and William Chaderton (1580–95) by forging charters using a copy of the college’s seal matrix. One of these suspect charters still survives in the archives of Manchester Cathedral.

One of the first tasks that faced Dee when he was installed as warden was to resolve the confusion around the college’s possessions and income. A draft of a commission that was drawn up in 1596, also in the cathedral archives, instructed Dee to investigate the poor state of the college and the authenticity of the college’s muniments, which were said to be ‘imbeseled, rased, diminished, defaced & kept from the sayd Warden & fellowes of the sayd Colledge to the greate loss & hinderance of the sayd Warden and fellowes’. In the manorial court of Newton (one of the college’s properties), Dee strove to recover lost tithes and prevent encroachments onto the college’s properties, although the process was inefficient: one offender, Richard Heape, had first appeared before the court in 1584 and was subsequently prosecuted by Dee at the court of the Duchy of Lancaster in London, but the case was not resolved until 1602. Dee also sought to define the parish boundaries, carrying out surveys and promoting the medieval custom of ‘beating the bounds’, fixing stakes, and engaging the most famous mapmaker, Christopher Saxton, to define and measure the town.

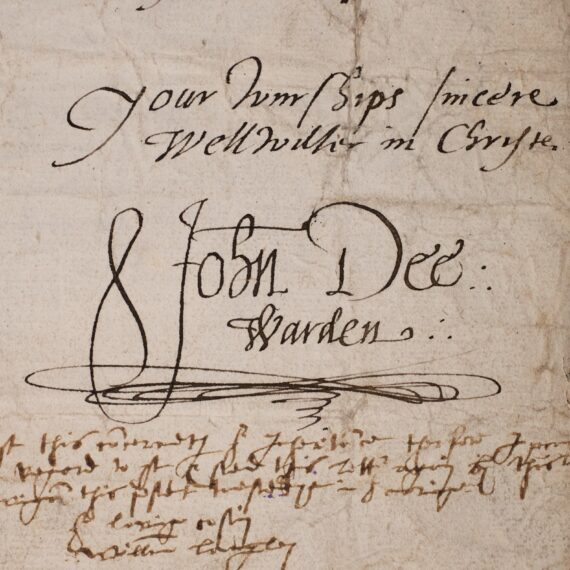

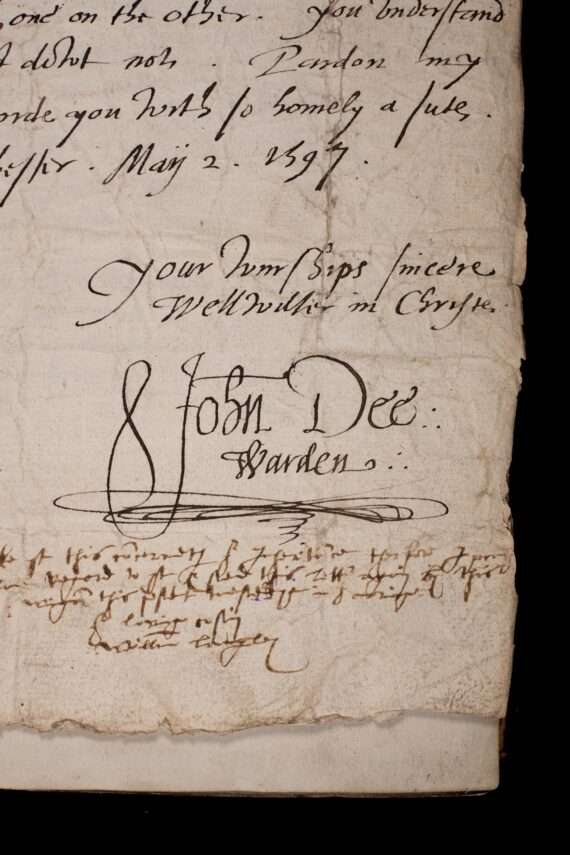

Figure 2: John Dee’s signature on a letter to William Langley, rector of Prestwich, dated 2 May 1597, concerning the bounds of the parish of Manchester (Chetham’s Library, Raines C.6.63, vol. 32, p. 9).

The problems around the college’s income were compounded by more general factors. The final decade of the sixteenth century was marked by pronounced economic depression and widespread famine across England, and four consecutive years in which the wheat harvest was poor meant that the country came to depend on imported Polish rye. In the aforementioned letter to Sir Edmund Dyer, Dee reported that he had received ‘barrels of rye from Danzig, some cattle from Wales, and some fish from Hull’, but complained that ‘so hard & thinne a dyet, never in all my life, did I, nay was I forced, so long, to tast’, nor had his servants ever had ‘so slender allowance at their table’. The general economic depression also resulted in inflation, leading to the general erosion of clerical incomes during this period as fixed monetary tithes and tithes of livestock came to count for less than they previously had. Dee found his stipend of four shillings a day as warden insufficient to support himself and his household, and he was repeatedly obliged to pawn his valuables in order to borrow money from local gentry, including Edmund Chetham.

All of these hardships could perhaps have been borne if Dee had found a welcoming community at the college, but his dealings with the fellows were acrimonious. The late sixteenth century was still a time of religious turmoil, and national troubles were played out on a smaller scale in Manchester’s college. The previous warden, William Chadderton, had concurrently been the bishop of Chester (1579–95), and he had placed the college at the heart of the Protestant reformation of Lancashire. In order to suppress Catholicism in the region, Chadderton was prepared to overlook a strand of Protestant nonconformity that had emerged within the college community, reflected in the refusal of several fellows to wear the surplice, a type of vestment that was regarded with suspicion by radical Protestants as a relic of Catholicism. Dee’s appointment as warden was partly intended to curb such nonconformity, and this brought him into conflict with the ‘turbulent fellows’. Dee described the fellow Oliver Carter’s ‘impudent and evident disobedience in the church’, possibly related to the wearing of the surplice, and Carter—who also practiced as a solicitor—threatened to sue Dee.

Dee left Manchester in 1598, and did not return until the summer of 1600. Despite his ‘heady displeasure’ with the college’s fellows in his absence, he reconciled with them, but within months trouble returned and he was called before the bishop of Chester’s commissioners to answer charges that the fellows had brought against him. In November 1604, he quit Manchester again. He may have intended to return, since his family stayed behind, but following the death of his wife Jane and potentially his three youngest daughters during a plague outbreak in Manchester the following year, he settled in his home of Mortlake. He was probably not disappointed to have left Manchester since he never found the peace and time for quiet study that he had sought in his appointment. Instead, his time in Manchester was defined by the troubles of the sixteenth-century college.

Blog post by Emma Nelson

3 Comments

Hurstel Edward

Very interesting, thank you

C

That was a tonic for the received knowledge of Dee. A practical man of affairs in a turbulent material world.

Susan Tanner

A really interesting read