- About

- Visiting

- What’s On

- Venue hire

- Catalogues

- Collections

- 101 Treasures of Chetham’s

- Digital Resources

- The Flowers of Histories

- A Book of Hours from France

- The Manchester Scrapbook

- Thomas Barritt of Manchester

- Art Treasures Examiner of 1857

- Manchester Association for Constitutional Order

- The North Western Museum of Science and Industry: Some Reminiscences by Richard Hills

- Criminal Manchester

- The Cup of Destiny

- Athenaeum Souvenir

- Middle English Manuscripts

- Manchester and Liverpool of Today

- Hollingworth’s Mancuniensis

- Memoir of Cecil Wray

- William Seward’s Diary

- The Anti-Monopolist

- Fishwick’s History of Rochdale

- Knyvett’s Defence of this Realm

- Tractatus de Nigromantia

- Axon Ballads

- Printed Books & Ephemera

- Archives & Manuscripts

- Prints and Photographs

- Blog

- Support us

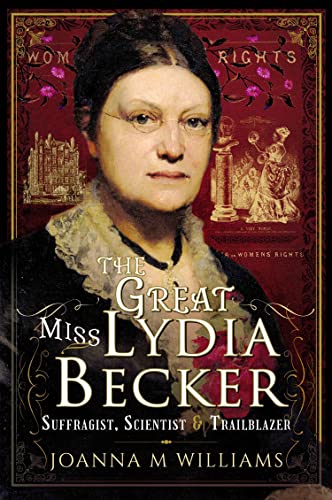

The Great Miss Lydia Becker: Suffragist, Scientist and Trailblazer

We were delighted this week to receive a copy of a new book on a Manchester heroine by Joanna M Williams, The Great Miss Lydia Becker. This fascinating piece sheds new and greater light on a figure whose untiring work as a suffragist has been a little overshadowed (perhaps as has the suffragist movement) by the militant suffragette movement. Joanna has made use of some of the political cartoons held here at the Library satirising and lampooning Becker and her political allies in Manchester, particularly the Quaker reforming politician Jacob Bright. (There’s more on the cartoons themselves on this blog post.)

As the foreword from the publishers, Pen & Sword tells us :

‘Fifty years before women were enfranchised, a legal loophole allowed a thousand women to vote in the general election of 1868. This surprising event occurred due to the feisty and single-minded dedication of Lydia Becker, the acknowledged, though unofficial, leader of the women’s suffrage movement in the later 19th century.

Brought up in a middle-class family as the eldest of fifteen children, she broke away from convention, remaining single and entering the sphere of men by engaging in politics. Although it was considered immoral for a woman to speak in public, Lydia addressed innumerable audiences, not only on women’s votes but also on the position of wives, female education, and rights at work. She battled grittily to gain academic education for poor girls, and kept countless supporters all over Britain and beyond abreast of the many campaigns for women’s rights through her publication, the Women’s Suffrage Journal.

Contemporary photograph of Lydia.

‘Steamrollering her way to Parliament as chief lobbyist for women, she influenced MPs in a way that no woman, and few men, had done before. In the 1860s the idea of women’s suffrage was compared in the Commons to persuading dogs to dance; it was dismissed as ridiculous and unnatural. By the time of Lydia’s death in 1890, there was an acceptance that the enfranchisement of women would come soon. The torch was picked up by a woman she had inspired as a teenager, Emmeline Pankhurst, and Lydia’s younger colleague on the London committee, Millicent Fawcett. And the rest is history’.

In January 1867 Lydia convened the first meeting of the Manchester Women’s Suffrage Committee, the first organisation of its kind in England. On 14 April 1868, the first public meeting of the National Society for Women’s Suffrage took place in the Free Trade Hall in Manchester. Becker was one of the speakers and moved the resolution that women should be granted voting rights on the same terms as men. She also founded the Women’s Suffrage Journal which she published from 1870 until 1890.

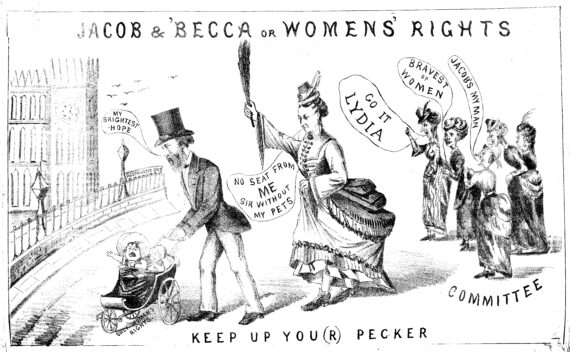

One of the many derogatory cartoons featuring Jacob and Lydia in our collection.

Becker also supported Lilly Maxwell in vote=ing in a by-election in Manchester in 1867. Lilly was a Manchester shopkeeper and ratepayer whose name had been included on the register of voters in Manchester by mistake. Lydia accompanied Lilly to the Chorlton Town Hall where the returning officer did allow her to vote. Becker immediately began encouraging other women heads of households in the region to apply for their names to appear on the electoral rolls but the practice was soon stopped when women’s suffrage was declared illegal in 1868.

Lydia was close friends with Jacob and Ursula Bright, both staunch supporters of women’s enfranchisement. Jacob Bright was a radical from a Quaker family of politicians, activists and reformers. Jacob stood unsuccessfully as a Manchester MP in the 1865 election then was elected in 1868. He was a suffrage campaigner. A Manchester Guardian article described women’s suffrage as Jacob’s obsession. ‘He brought it into all his speeches, much to the annoyance and even dismay of some of his staunchest supporters. “Jacob is at it again!” a affectionate friend would whisper: and it was true. he is always “at it”.

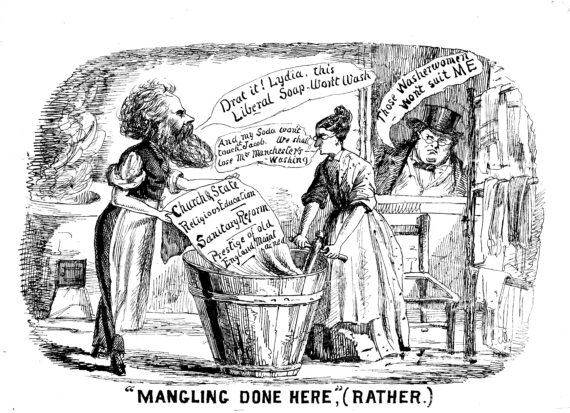

This is Lydia and Jacob depicted as destroying the values of church and state.

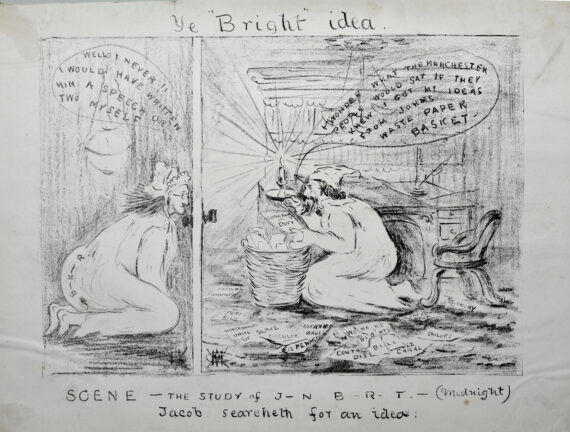

Becker and Bright (standing as Liberal candidate) made suffrage one of the major issues in the 1868 general election. Their views attracted public scorn and suffrage came in for particular attention in the political cartoons that lampooned Bright’s policy proposals. The cartoonist’s representations are vicious: female politicians were not spared unnecessary ridicule, and with their focus on exaggerating physical features, cartoonists often added an element of misogyny. Some of the portrayals of Becker are clearly intended to be upsetting, and reflect the view among many at the time that women had no business speaking up in public.

As Linda Walker’s article in the Dictionary of National Biography suggests, cartoonists found it all too easy to belittle and insult Becker: ‘Physically stout from early womanhood, her broad, flat face, wire-rimmed spectacles, and plaited crown of hair were a cartoonist’s delight, and she was much lampooned in the popular press.’

Another humiliating cartoon of Jacob and Lydia titled ‘Ye Bright Idea’.

Bright was elected to parliament as Liberal MP where he continued to campaign actively for women’s suffrage, becoming leader of the suffragists in parliament in 1868. He introduced the first suffrage bill to extend parliamentary suffrage to all women. While Parliament refused to give any ground on women’s suffrage at national level, however, the suffragist had their victories. Bright was able to get an amendment through in committee that granted women the right to vote in municipal elections, and in 1880, Becker, Bright and others campaigned in the Isle of Man for women to receive the vote in the House of Keys elections. This venture proved successful when the Isle of Man for the first time included women in the elections of March 1881.

In addition to her key role in the suffragist movement, Lydia was an accomplished scientist and corresponded with Charles Darwin. She sent some botanical specimens to him from the Manchester area, also forwarding him a copy of her “little book”, Botany for Novices of 1864. However, she gained recognition in her own right for her scientific contributions, being awarded a national prize in the 1860s for a collection of dried plants prepared using a method that she had perfected so that they kept their original colours.

She went on to give a botanical paper to the 1869 meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science. The following year Lydia founded the Manchester’s Ladies Literary Society for women to study scientific matters.

Becker was strongly in favour of a non-gendered education system in Britain, and campaigned more strenuously for the voting rights of unmarried women, believing that women connected to husbands and stable sources of income were less desperately in need of the vote than widowed and single women. In the 1870s, she participated in the campaign to repeal the Contagious Diseases Acts and was a member of the Vigilance Association for the Defence of Personal Rights. She also organised a landmark repeal meeting during the Free Trade Hall debate. In 1890 Becker visited the spa town of Aix-les-Bains, where she contracted diphtheria, and died at the age of 63. As a mark of respect, rather than continue publishing in her absence, the staff of the Women’s Suffrage Journal decided to cease production.