For the private amusement of Chetham’s Library

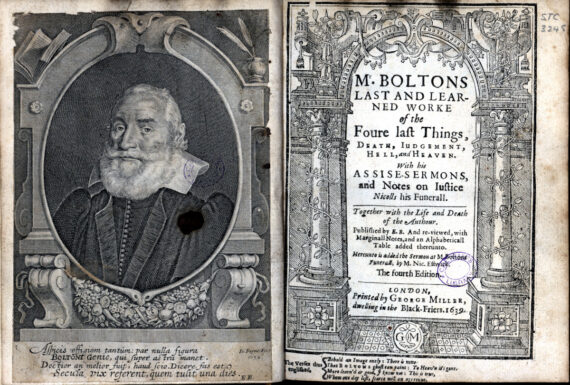

2 CommentsEarly last year, we celebrated the appointment of Julianne Simpson, as Chetham’s new Librarian, with an exhibition entitled ‘Chetham’s Librarians: Lives and Legacies’.

As part of the research for this exhibition, I had the wonderful opportunity to delve into some of the past librarians’ diaries that we have in our collections. Most of these are quite dry, and relate strictly to business: reader appointments, shelving numbers and committee meetings. They were hard to extract any personality from the pages, to enlighten us as to the Librarian’s character. However, the diaries from the late 1940s are an entirely different matter.

As the second world war was coming to an end, the decision was made to re-open Chetham’s and prepare to take in reader appointments again. After years of the Library being boarded up to protect the windows, and furniture and paintings being stored in safer locations, the position of Librarian was offered to Miss Hilda Lofthouse in 1944.

Left: Hilda Lofthouse and cat. Right: Pauline Leech, photographed at Bletchley Park.

At the time of her acceptance, Hilda was in her early 30s and working for the foreign office, and so her position was postponed until after the war had ended. Not long after that, it was decided that Hilda would require some much-needed help to get the Library back in working order, and the perfect candidate applied for Assistant Librarian…

Miss Pauline Leech had been working as a code breaker at Bletchley Park throughout the war, and despite her father’s attempts to persuade her to stay on at Bletchley after the war, Pauline was determined to train as a Librarian.

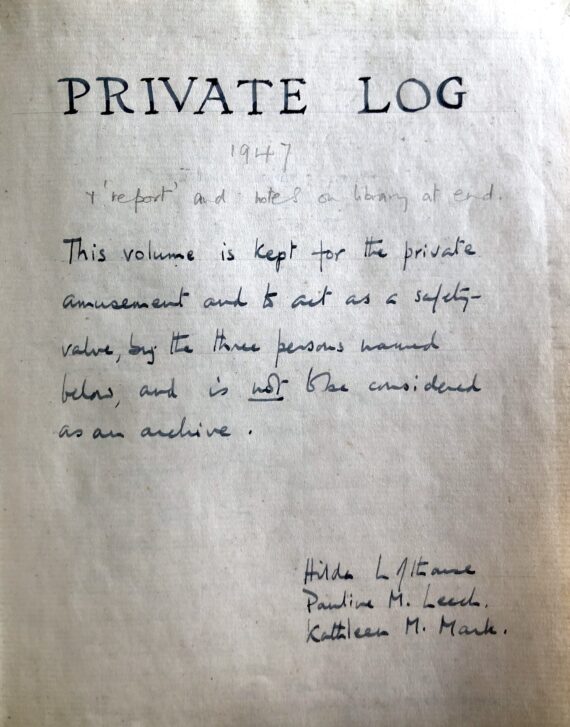

The first page of the 1947 diary

Our first Librarian’s Log book by Hilda and Pauline (and intermittently Kathleen Monk) begins in 1947, and is continued in annual diaries right through to 1975. Despite the notice written on the first page, the diaries did indeed become part of the Library’s archives after Pauline’s death in 1994. I, for one, am very thankful they were!

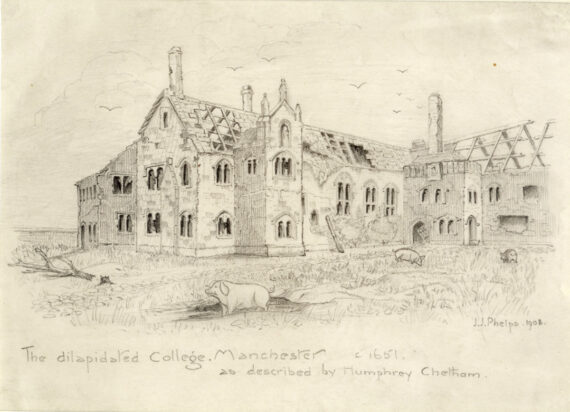

Each entry, whether short or long, gives us a wonderful snapshot into their everyday life in the Library. The arduous task they had, in cleaning and organising the Library after the hostilities, must have been exhausting. We know from Library Committee meeting notes from the time, that the windows of the medieval building had been boarded up to protect the building from broken glass, and the threat of gas to the staff during the war. However, this had meant that the building and its collection lacked sufficient ventilation during these years, and a great deal of care for the collection was needed after the Library was re-opened.

However, it looks as though the women enjoyed the challenge, and they kept a tally of their achievements at the top of each page; rooms cleared, collections catalogued, shelves re-organised. There was only one real threat to their work… the Readers!

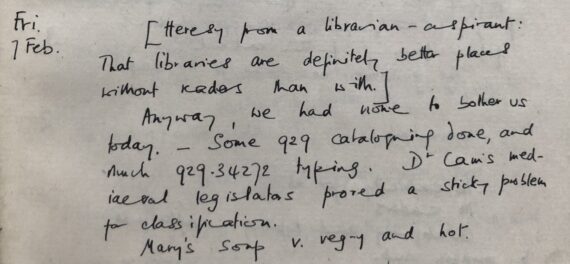

‘Fri 7 Feb [Heresy from a librarian-aspirant: That libraries are definitely better places without readers than with]’ – Diary entry from 1947.

In addition to these disruptions, was the work taking place in the building, on clearing out the fire-damaged Governor’s rooms, and repairing the roof, which had been damaged during the blitz in December 1941. In many of Hilda and Pauline’s entries, they mention the noise of the workmen and of the dust they traipsed in around the building, however it was more often than not, the cleaner, Mary, who was doing the complaining.

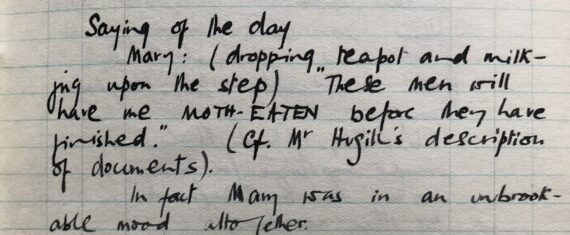

‘Saying of the day Mary: (dropping teapot and milk-jug upon the step) “These men will have me MOTH-EATEN before they have finished!” In fact Mary was in an unbrookable mood altogether.’ – Diary entry from Tuesday 24th Feb 1948

I have to say, the entries containing anecdotes about Mary, have become my favourite passages to read. One particular favourite of mine is from Saturday 26th April 1947, where Pauline writes about how ‘Mary was in a strongly reminiscent mood as she dusted us this morning. We heard 2 of the generations of rats that had lived and died in the Library and school – and since Mary saw their skeletons lying mouldering on the bookshelf tops, she has never been able to eat rabbits!’.

Other entries mention regular visitors to the Library, Feoffees (trustees), long-term readers, and colleagues working at John Rylands or Central Library. Some of these names we recognise from meeting notes, or letters of business exchanged, but through these diaries, we hear a little bit more about their personalities.

For instance, they hint at not getting along with the Feoffees all too well, except for Col. Riddick, who appears to be a favourite of theirs.

‘A handsome gift received today, by the Librarian and her assistant – viz. One large egg each from one of the Feoffee, Col. Riddick!’ and ‘ A day of ‘excitements’. Col. Riddick with a basket of daffodils discovered floating about the building – and generously handing out the daffodils.’

I can’t speak for the rest of the Library staff, but I, for one, would love some someone to float about the Library handing out daffodils and freshly laid eggs! It would certainly make a change from the excitement of freshly laid mousetraps.

One thing I can say about Hilda and Pauline’s diaries, is that no matter what is going on outside the medieval walls of Chetham’s Library, nothing really changes within.

We still have problems with the heating, the electrics, the leaking roof, we’re very familiar with the spiders and mice that make this building their home, and we’re always dusting, dusting, dusting! There’s something quite warm and familiar about that fact, that in the 370 years Chetham’s Library has been open to the public, that the staff have been facing the same trials and tribulations all these years, and in order to work here, you must possess a good sense of humour!

Caption on reverse: ‘HL + PL on Chetham’s Library roof. Victoria St. and Railway Offices in background. “Goldie” from Reading Room. 5.8.1969’

By Siân-Louise Mason, Visitor Services Coordinator at Chetham’s Library